Tags

Was Beowulf the product of a poet’s lively imagination? Borrowed from tales told by the fire? Based on actual historical events? The more I look into the origins of oldest epic in the English language, the more I believe it is a combination of all of the above.

Beowulf was composed somewhere between the middle of the seventh century and end of the 10th, a period that overlaps with the migration of peoples who lived in Germany and Scandinavia. Faithful readers of the poem will remember that it’s set in Scandinavia, so it should come as no surprise that the migrants took their stories with them. They maintained cultural ties to the Baltic in the fifth and sixth centuries, and Anglo-Scandinavian trade in glass claw beakers (fancy drinking vessels) continued into the seventh.

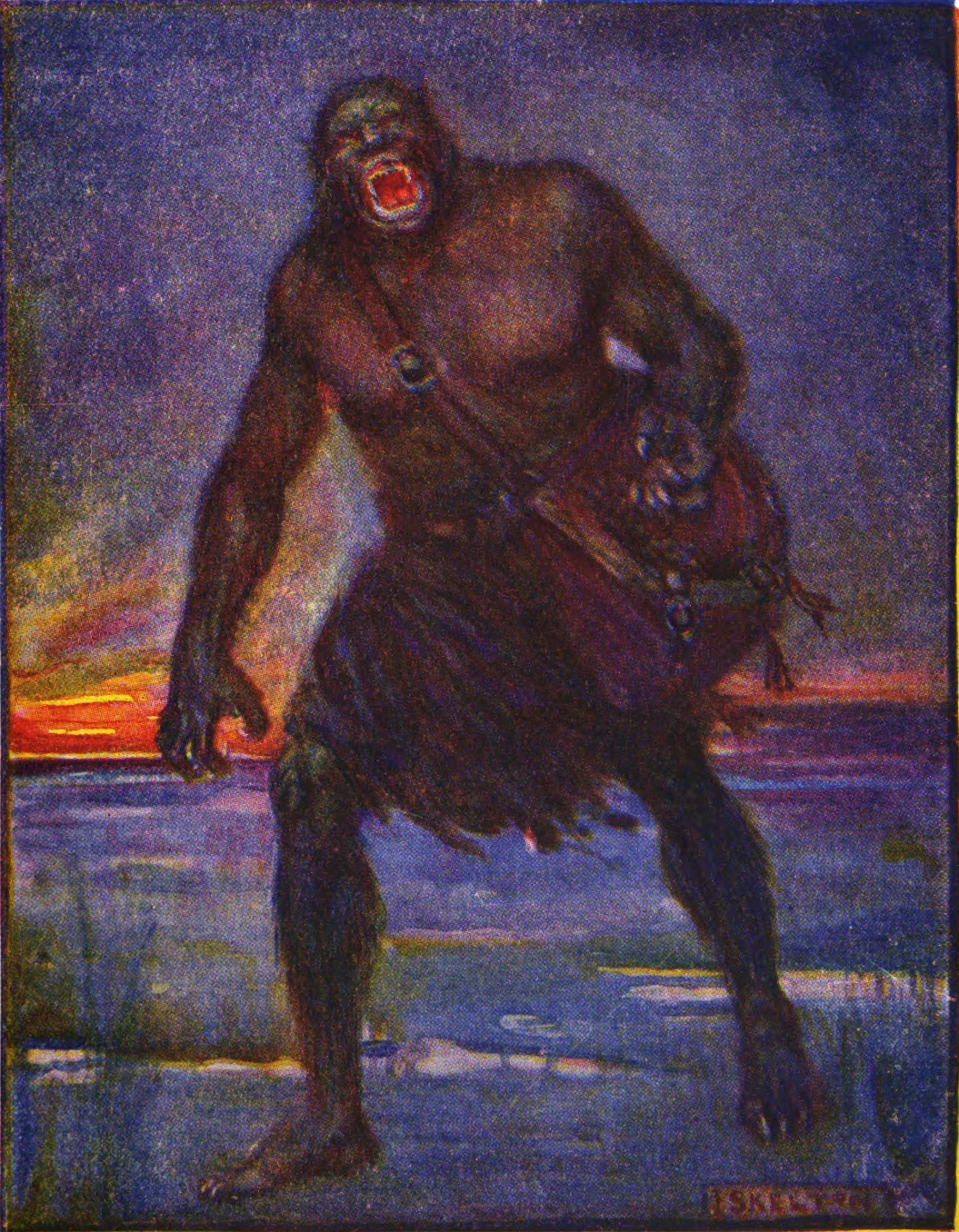

The folk might have told tales about a ruler’s death in battle on a foreign land. They might have made references to a sixth century enemy from today’s Sweden. They might have woven in objects from daily life such as harps and helmets. If the purpose was to entertain rather than educate during long winter nights, someone might have embellished the tale with a hero and monsters.

Today, we have tantalizing clues to where the poet borrowed from history. Gregory of Tours’s History of the Franks recounts a Danish-Frankish war, estimated to have occurred around 523, in which the Danish king was killed – similar to passages describing the death of Hygelac, Beowulf’s kinsman. A high-status burial mound in Sweden may be the final resting place of Ohthere, a king who is named a few times in the poem. Artifacts from Sutton Hoo are consistent with objects mentioned in the epic.

We might never know the true origin of the oldest epic in the English language and will likely never know who wrote it. But even with its mysteries, it reveals something valuable: the culture of its writer.

Through the poem, we see that the characters in Beowulf are Christian but practice their faith differently than most modern day believers. They are much most interested in justice than mercy. When Grendel, the monster descended from Cain, wreaks havoc, they want vengeance. The pagan influence was still strong. The image of the boars on the helmets were a sign of strength as well as beast sacred to a god, and the characters burned their dead, piling grave goods on the pyre.

Whoever wrote Beowulf likely meant to entertain his contemporaries, perhaps even a lord looking for a diversion or claiming descent from the hero to assert power, but the poet left a gift for all generations.

Sources:

Beowulf, translated by Seamus Heaney (very good reading, even if you’re not doing research)

The Origins of Beowulf: And the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia, by Sam Newton

“Formation and Resolution of Ideological Contrast in the Early History of Scandinavia” (PhD thesis) Carl Edlund Anderson. University of Cambridge, Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic (Faculty of English)

Originally published April 21, 2014 in English Historical Fiction Authors.