Tags

Early medieval women were far from passive damsels waiting for a knight to rescue them.

Of course, this time period is hardly an ideal time for women: childbirth so risky expectant mothers were urged to confess their sins before they went into labor, fathers choosing whom a girl would marry, age 13 considered marriageable, wife beating defined as a right.

But to say that girls were nothing but pawns valued only for their ability to produce sons grossly oversimplifies medieval women’s reality, and it gives a false impression of that women in this era were merely victims who contributed little to their society. Truth is, they tried to shape their situations.

In the mid-eighth century, Saint Boniface depended on both nuns and monks to assist him in his mission to strengthen the church in Europe and spread Christianity. The women left the security of their abbey in Britain and took an uncomfortable, hazardous journey to areas east of the Rhine. Those who were appointed abbesses were not only pious. They were in a position of influence and needed to act independently.

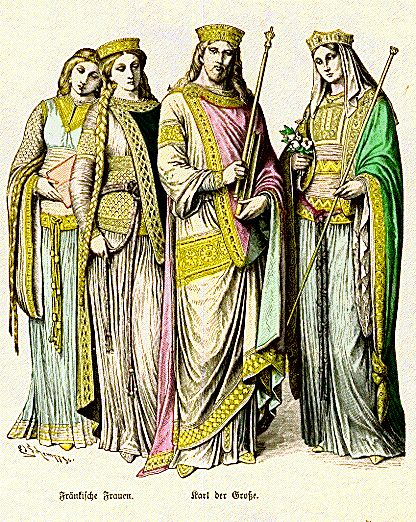

On the secular side, aristocratic women did more than produce an heir, although husbands did try to set aside wives unable to bear children. The queen’s role was “to release the king from all domestic and palace cares, leaving him free to turn his mind to the state of his realm,” according to the ninth-century treatise The Government of the Palace. In an age when the personal and political were intertwined, the queen was the guardian of the treasury, and she controlled access to her husband. When houseguests were foreign dignitaries, royal hospitality was key to international relations.

Bertrada, Charlemagne’s mother, had been her husband’s full partner as they seized the kingdom of Francia in a bloodless coup. After he died, she became a diplomat whose most important mission was peace within her own country. Her sons, Charles and Carloman, each inherited half the kingdom, and Bertrada needed to keep the rivalry between the brothers, ages 20 and 17, from escalating to civil war.

Bertrada is just one example. After Carloman died of an illness and Charles seized his dead brother’s lands, the widow Gerberga was not about to let her toddling sons lose their kingdom without a fight. Likely a teenager, Gerberga crossed the Alps with two little boys in tow and sought the aid of Desiderius, the Lombard king furious over Charles’s divorce from his daughter. Later, Charles’s third wife, Hildegard, might have been the one to convince him to make her sons his heirs, perhaps excluding the son by his first marriage.

These historic women are why the heroines of my novels try to solve their own problems, even when it’s painful. Alda in The Cross and the Dragon has a household to run and servants to keep in line. She bargains with the merchants and gives to charity. Leova in The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar is a peasant, but at the beginning of the novel, she is a free woman with responsibilities, including children to raise and a house and farm to maintain with her husband. When she is betrayed and sold into slavery, she resents being seen as property and yearns to be a respectable woman again.

The existence of slavery meant that some women were chattel, but so were their male counterparts. But as you will see in this excerpt from The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, even slaves could use their wits to get their way.

***

Looking down, Leova stepped forward, her limbs stiff. Her thoughts were consumed with worry that Deorlaf would rush forward to defend her, just as Derwine would. She glanced over her shoulder.

Sunwynn stood rigid. Deorlaf’s body was tense like a cat ready to pounce into a fight. His hand strayed to his belt where his eating knife used to be. Deorlaf, don’t!

“Peace, Deorlaf,” Ragenard called over Leova’s shoulder. “I mean your mother no harm.”

She felt Ragenard’s hands on her sides and started. The touch against her ribs was gentle. Turning toward Ragenard, she met his gaze. She saw no malice in his amber eyes. A smile flickered on his lips. Then, he straightened and dropped his hands.

“You have cared for her well, my lord,” said Ragenard, his chiseled features impassive. “She is comely and has the temper I seek. So many other serving women are crushed and almost useless or lazy and willful. But this colt is worth more than the best maidservant.” He patted the sleek animal’s shoulder. “He is in his prime, obedient to the rein, yet has enough spirit to charge into the hunt.”

Leova seized the opportunity. “You’re right, Ragenard,” she said, hoping to keep the tremor from her voice. “A horse is worth more than me. Take the children as well.”

“Be still, woman,” Pinabel snarled. “Or I’ll rip out your tongue.”

Originally published Sept. 25, 2014 on Every Woman Dreams…

Sources

Medieval Women Monastics: Wisdom’s Wellsprings, edited by Miriam Schmitt, Linda Kulzer

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walters Scholz with Barbara Rogers

“Pavia and Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century,” Jan T. Hallenbeck, published in 1982 by Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

“Women at the Court of Charlemagne: A Case of Monstrous Regiment?” Janet L. Nelson, The Frankish World 750-900

“Family Structures and Gendered Power in Early Medieval Kingdoms: The Case for Charlemagne’s Mother,” Janet L. Nelson. Women Rulers in Europe: Agency, Practice and Representation of Political Powers (XII-XVIII)

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Pierre Riche

I think it’s important to mention the socio-economic class. I seriously doubt that an artisan would say “no” to an extra set of strong hands. It seems that when historians talk about the lot of women in a specific area, they focus on the ruling class. In communities where you had to work for survival, every able bodied individual, regardless of sex, was valued. If the woman was strong and productive, she was more valuable, even if she had a strong temper.

LikeLike

One reason for the focus on the ruling class might be that they were the people who got the ink. And political marriages had the fate of entire peoples at stake. Among all classes, each situation would vary. An artisan seeking wife might value ability and competence over meekness.

LikeLike

That only proves that gender roles and gender polarization in general are for the privileged class. A meek and useless wife would frustrate a farmer. In Baltic rural communities violence against women or any other member of the community was considered a terrible affront. You don’t damage able-bodied individuals who contribute to the survival of the community.

LikeLike